In last month's New Yorker food issue, Nicola Twilley takes a jaunt through sensory science with Charles Spence, the psychologist who heads Oxford's Crossmodal Lab. Spence's research investigates the multisensory aspects of perception, especially the perception of flavor. Beer tastes more bitter when bass is booming from the stereo.

Twilley's article looks at how food companies apply Spence's research to packaging design: in order to engineer cans for energy drinks, for instance, whose hiss when opened is pitched to evoke masculine fortitude, or low-sugar chocolate bars whose red wrappers dial up sensations of sweetness. In other words, shaping the container to influence the perceived qualities of the thing contained. For manufacturers, research like Spence's seems like a way of bringing some scientific rigor to the fuzzy, intuitive art of container design, perhaps minimizing the high mortality rate of new products. Spence himself keeps "a rogues' gallery of failed products" on display in his office, brief-lived merchandise whose commercial death warrant was signed, according to his diagnosis, by design decisions that failed to account for the perceptual effects of colors, sounds, and shapes on consumers' experiences of flavor.

But food packaging has long been an engineering problem with recognized sensory dimensions and consequences — though not exactly the kinds of sensory effects studied by Spence's lab.

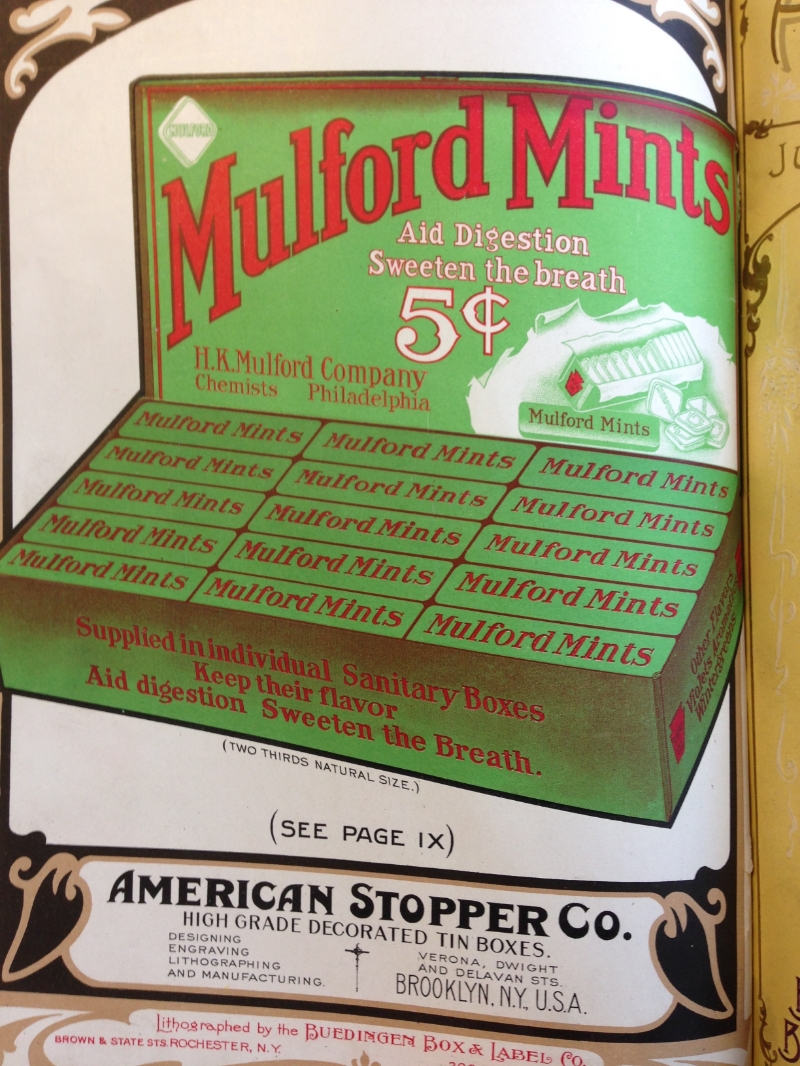

One of the beautiful color lithographed advertisements in American Perfumer & Essential Oil review, this 1913 ad for Mulford Mints draws attention to their "individual sanitary boxes" which "keep their flavor."

Consider the package for a moment. Packaging itself defines the category of "processed food" more than any other aspect, and sharply distinguishes the foodways of industrial modernity from prior modes of eating and living. (For instance: Labels! The whole visual/informational superstructure of the modern food industry — and a good part of regulatory agencies' authority — depends upon the infrastructure provided by the package, which serves as the slate upon which the enticements and warnings and "facts" can be inscribed.) Think about the vast and heterogeneous category of food made in factories, now and in the past: Leibig's Extract of Beef, Heinz's 57 Varieties, Uneeda Biscuits, Land O' Lakes butter, Campbell's Tomato Soup, Diet Dr. Pepper, Midnight Cheeseburger Doritos. Each comes in its own, standardized, (almost always) inedible, rarely reusable container. Sometimes there are even containers within containers: colorful, printed cartons enclosing translucent bags of Wheaties, or transparent sleeves of Oreos, or microwaveable black plastic trays of Lean Cuisine, whose frosted slab of lasagna or sesame chicken is kept immaculate by a heat-bonded layer of crystalline film.

The importance of finding the right container; in this case tin foil bags for coffee. Spice Mill, 1915.

Rather than thinking of food and package as two dissimilar kinds of things, brought together at the end of the production line only to be torn asunder in the kitchen, it is important, I think, to consider both as integrated components of a single system. The inedible package profoundly affects our experience of the edible contents within, defining the possibilities and scale of industrial food production, as well as setting our expectations for food that tastes "factory fresh," flavorful, familiar, reliably consistent.

Packages are technologies of preservation, forestalling not only actual rottenness, but ideally also maintaining food in a sort of homeostasis until the actual moment of consumption. Long adapted to keeping out moisture, oxygen, vermin, and other assorted crud, in the twentieth century, the package becomes a deliberately designed tool of flavor control.

Flavor control? Yeah, cause flavor needs to be controlled. Volatile chemicals, those aromatic agents that deliver a large part of our flavor experience, are cosmopolitan and promiscuous. They are tireless travelers, and keep all kinds of company. Packages were designed to keep volatiles in the package, and to protect them from oxidative and other changes. Research into stale coffee led to air-tight packages filled with inert gas, that could keep ground beans tasting "fresh" longer. Glass milk bottles were replaced with opaque containers in part to prevent the disconcerting, tallowy taste that sometimes developed when milk was exposed to sunlight.

In the flashy world of food packaging, don't forget about the humble paper bag!

But a package's membrane is penetrable from both directions, which also allows inauspicious odors to creep in and settle down. Tracking down the source of mysterious "off-flavors" that tainted packaged goods was often described as a kind of detective work. As early as the 1930s, chemical consulting firms offered their sleuthing services to companies to track down the source of that musty smell in cigarettes, or that weird flavor in certain shipments of cocoa. (Both real cases handled by NYC consultants Foster D. Snell in the 1940s. The cigarettes were contaminated by benzene hexachloride, leached from a bag of insecticide that had been packed alongside the smokes during shipping. The cocoa's weird aroma was due to inks used on its colorful label.)

The new scientific attention to the flavor and "keeping qualities" of food fueled research and interest in new materials. Glass jars and tin cans were joined by squeezable tubes, waxed and laminated cardboard, and, especially since the Second World War, plastics, such as cellophane, polyethylene, polyvinyl, and other synthetic polymers and composites.

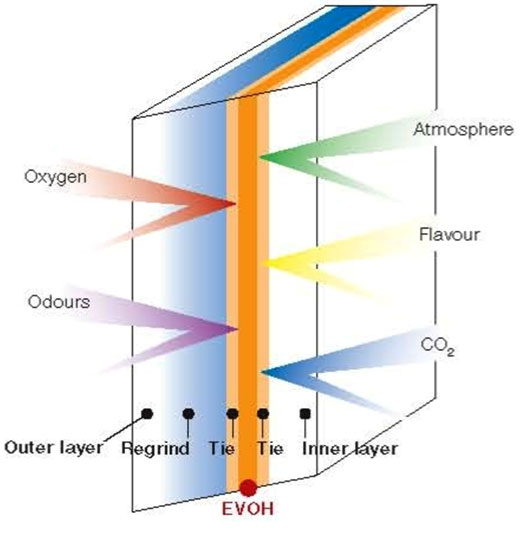

The common material EVOH - ethyl vinyl alcohol - a copolymer of ethylene and vinyl alcohol - in action at the center of this multi-layered co-extruded packaging material.

The new plastic materials could be cheap, light, and flexible, durable and colorful, but they also had liabilities. Consider that packaging material isn't just a passive membrane, but has its own sensible qualities, and its own proclivities to form attachments, to cling and react. For instance, some commonly used plastics have a tendency to bond with certain flavor chemicals, upsetting the carefully calibrated flavor balance engineered by flavorists. The technical term for this is "scalping," I kid you not. Polyethylene, one of the most common plastics used in commercial packaging, is a notorious top scalper. The material lining the gabled tops of Tropicana orange juice cartons were found to be scalping the top-notes off the OJ within, which led manufacturers to move to materials that would not absorb the citrusy linalool and limonene within their clingy matrix.

The proliferation of chemicals in the world, and the complexity of the production and supply chain, means increasing numbers of opportunities for foods to be tainted. (Here's a great article by Sarah Everts on this subject.) Lubricants used in the production of beer cans can linger on the can, reacting with the beer to produce rancid flavors. Fungicides and microbicides used to treat wooden pallets can sometimes react to form chloroanisoles, which can leach through cartons stacked on top of the pallets to impart a moldy odor. A cat urine off-odor that contaminated some cooked ham products was found to be caused by printing inks that had migrated into the laminate film used as packaging, reacting to form the pissy-smelling 4-methyl-4-mercaptopentane. In 2010, Kellogg's recalled 28 million boxes of Froot Loops, Apple Jacks, and other cereals, because a weird smell — described variously as waxy, stale, metallic, and soap-like — had been reported, causing a handful of consumers to feel nauseated and vomit. It took quite a bit of sleuthing to determine that the cause was inks used on the exterior of shipping boxes, which had migrated through three layers of packaging to taint the cereal within.

Before sensory psychologists like Charles Spence can work their tricky magic on package design, the business of flavor chemists depends on packages that are engineered to preserve and protect the sensory qualities of food.

And to close out this little reflection on the increasingly intimate relationship between the container and the thing contained, the thing contained and the container, I'll leave you in the capable hands of Thurber. In "Here Lies Miss Groby," his 1942 rememberance of his old English teacher, (an essay which often haunts my reverie), he presents this joke as an example of reverse metonymy, of taking the thing contained for the container:

A: What's your head all bandaged up for?

B: I got hit by some tomatoes.

A: How could that bruise you up so bad?

B: These tomatoes were in a can.